Precious Girl

All children believe themselves to be special. In time they are slapped by the truth: they are denied something they want, or they are replaced by a baby sibling, or they look around and notice the other boys and girls in their village are just like themselves. In our community the men fish and build, the women produce food and raise children, and the young ones grow up learning to do these things. But one child is always the fleetest runner. Another has the fastest mind, and another the quickest tongue. Certain gifts are undeniable.

I was the best-loved of all the children on the island.

It was my beauty that drew attention initially. From the time I was a baby, adults gazed at me with adoration, begged to hold me, made fools of themselves to win a smile from my toothless mouth. The village priest heard of me and paid a visit to our home, an honor from which my mother never recovered. He blessed me and our hut, and said that my destiny would be very special indeed. My parents had named me at birth, but from then on everyone called me Precious Girl.

As I grew into a child, my beauty grew, too. I could not walk through the marketplace without everyone we passed reaching out to stroke my hair. And it allowed me certain honors. I did not have to take part in tedious work around the house. Behavior that would have gotten my sister punished was excused in me. The last piece of mango was always mine.

I made the other children play what I wanted to play, I took their possessions, I demanded to win every game. If anyone showed reluctance, I needed only tell an adult. Many children were beaten due to my complaints. I was unaccustomed to disappointment.

It was a shock the day I was told no. While racing around the beach with the other children I saw the older boys taking out boats. I claimed a spot in one of the canoes, but they brushed me aside. As the boys paddled away without me, my disbelief turned to fury. I cried until my body was fiery with rage. I whipped fists and fingernails at anyone who approached. The boys headed out to sea, and I screamed until my throat was shredded. Someone brought my mother all the way down to the beach, and eventually she took me away from the water’s edge. The boys were mere dots in the distance by then.

At home, I sat exhausted and shaking while my mother stroked my hair. Someday, she said, your greatest wishes will come true.

~

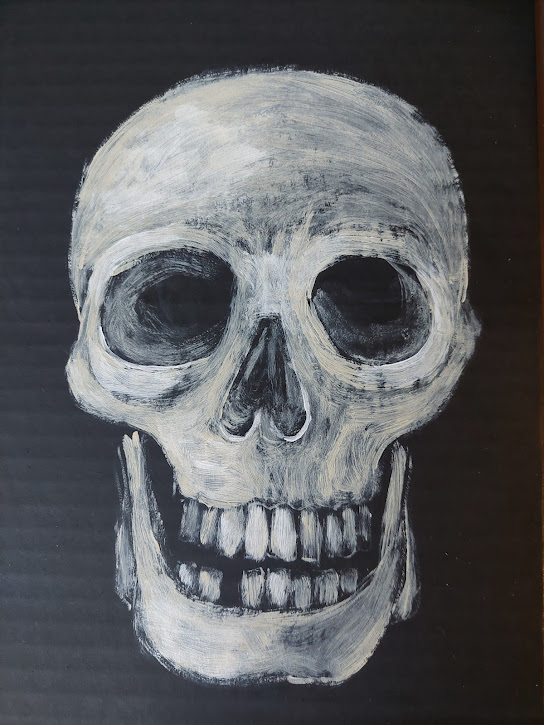

One day my grandmother was teaching me how to open oysters. Look closely, little one, she said. And then the knife slipped and sliced my cheek.

I howled and howled, a bit from the pain but mostly because of the look of horror on my mother’s face. My father shouted at his mother. I could see my blood on the knife.

Women from all over the island came to our home. They stood over me and argued about which balm to rub on my skin, which mountain plant to burn in my presence. Soon I was ready to go out to play, but my mother kept me in her arms, breathing foul-smelling smoke. My grandmother sat in the corner, her blanket drawn around her, watching silently.

In the end I had a small pink scar on my cheek. The priest came to my house to inspect it. Somehow, he said, our Precious Girl is even more beautiful because of it. My parents sagged with relief. He blessed the house again before he left, and my mother wept with joy.

~

The mountain in the center of the island was off limits even to the big boys who took the boats into the sea, but I roamed the rest of my world freely: the huts and gardens, the beach and market. Everyone knew me. I felt protected.

Still, I had moments of doubt. I wanted the children to look at me the way their parents do: with love and excitement, honored to be near me. They all played with me, but I sensed a reluctance in some of them. The cruelest of all, I felt, was my sister.

I wanted to be her friend, but whenever I reached out to her, envy made her respond with a sneer. My parents and grandmother would coddle me, and she would sit nearby and glower.

When the conversation turned to me, she tried to insert herself. She was better behaved, smarter, a better daughter. When my parents remained uninterested, she turned to bad behavior. She took little things. She lied. While playing, she would leave the safe areas. Once she brought home a flower and tickled my face with it. She said she picked it halfway up the mountain. When I told my parents they beat her until I begged them to stop. She despised me even more.

My grandmother was kind to my sister, but I remained her favorite. For months after the accident with the knife, my mother sent the old woman furious looks and tried to keep us apart. My mother’s anger made me press closer to Grandmother’s sun-dark skin, wrap her gnarled hands around me. My father forgave his mother, and eventually it seemed my mother did, too.

One night my grandmother woke me while the rest of the family slept. As she put her finger to my lips I could feel the tension in her body. Silently we crept out of the house, past the rest of my sleeping family. I was excited. On the walk past our neighbors’ huts I tried to ask her where we were going, but she kept shaking her head. I had never seen her crooked body move so quickly. I followed her down the path to the beach, and when we reached it, I saw the moon on the water, the darkness sapping everything of color, the canoe against the sand.

A boat! I ran ahead of her to it. A paddle lay inside it, and a sack. While I waited for her to catch up I peeked inside: loaves of bread and dozens of pieces of fruit. My grandmother limped across the sand to me. Get in, she panted. And get down.

But I wanted to sit up like the big boys did. She began pushing the canoe into the water, so hard she was grunting and shaking. Because I was sitting up and facing her, I could see my father and the other men coming down the path and running onto the beach.

I waved to my father. He was shouting, but I could not understand over the sound of the waves. I am going in a boat! I called.

Get down, little one! my grandmother shouted in a voice I did not recognize. She pushed until the men came and pulled her away from the boat. It had never left the sand.

There was so much shouting I could not understand it. My father yanked me out of the canoe and stood staring at his mother. A man was holding her arm on either side, but she was not struggling. She was looking down at the sand. I thought she was crying.

My father called over one of the men, a neighbor of my family, and handed me roughly to him. Take her home, said my father.

The neighbor carried me away from the beach, up the path. Before the trees blocked my view, I could see my father walking towards my grandmother.

At home, my mother squeezed me tight, my sister glared at me, and then we all sat up drinking tea until my father came home. He walked in the door alone. Where is Grandmother? I asked. I began to cry. Did she go in the boat without me?

My sister pinched me and my mother sent me a silencing look. My father did not look in my direction. He was addressing us all when he said in a choked voice, We will never mention her again.

~

It was some time later that the ground began to shake.

To the children, it was strange and exciting. We would run over the shaking earth, fall to the ground, pretending to be knocked over by its power. Giants, we said. Gods. We saw nervous looks among the adults, caught the tail ends of hushed conversations. They told us to stay close to home. Even my sister limited her wandering.

One morning I woke up coughing. The sky was gray. But the mood among the people was joyous. All the aunties in the village came over, and our hut was filled with fruit and singing. They prepared a bath that smelled of oil and flowers, and they washed my skin and braided my hair and tucked flowers among the strands. Their busy fingers and soft skin and smiling faces were all for me.

And then we all went outside, and the men and children of the village were there. Despite the heat and dusty air we all gathered and laughed and ate fruit and sang the songs of my choosing. When the priest arrived, we fell to silence. He approached me. I could feel my mother standing behind me, quivering.

He was holding a goblet, and he said a few words, things about prosperity and safety. While he spoke I looked around at the people, smiling at my friends, noticing my sister was not in the crowd. The priest lowered the goblet and handed it to me. Drink, Precious Girl, he said.

There was not much in the cup, and little flecks of dust floated at the top. I took it in my mouth and did not like the taste. An exclamation rippled through the crowd, and while their attention was elsewhere I spit the juice on the ground. Nobody saw me. When I looked up I saw what had drawn their attention: four men had arrived carrying a fancy chair above their heads. It was decorated with carvings.

A boat, I thought. I looked to my mother for permission.

It is for you, my mother smiled.

The crowd parted to allow me to reach it. The men had let it rest on the ground. The chair was supported by the poles they had carried on their shoulders. I ran my fingers over the wood, along the carvings. I looked up at the priest, and he nodded. I sat down on the seat.

Then the men lifted it to their shoulders. I was taller than everyone! I could see them all. Were it not for the ash in the air, I would be able to see all the way to the beach, as far as the mountain in the center of the island.

When we started moving, the jostling made me laugh. Everyone I had ever met was smiling at me, waving, sending their love to me. I waved back at them as I was carried off.

Just as we were leaving, my sister ran out of the trees and stopped at the edge of the path. She began to cry as I was carried past. Surely she was envious of my chair. It is for me, I called to her. Just for me.

I expected the men carrying me to walk to the marketplace, or perhaps the beach, but instead we walked into the trees. Ahead of us walked the priest.

I want to go home now, I called up ahead. He did not turn his head. Two men lifting the chair were behind me, so I could not see them, but I informed each of the men I could see that it was time to turn around. Neither responded.

I began shouting and screaming, but they did not obey me. I kicked the head of the one on the right, and he called something to the priest. He stopped walking and they lowered me to the ground.

I am done, I said. Take me home.

Drink this first, he said, pulling a bottle from his belt. I noticed a knife there, too, and I didn’t like it. He handed me the bottle, no goblet this time. Drink.

If I drink this, I said, you will bring me home?

Yes, he said.

I took the smallest possible sip. It tasted warm and bitter.

More, Precious Girl, he said.

While I was taking another tiny sip I heard him mutter something, and then one of the men pulled my head back and another lifted the bottom of the bottle. The awful taste flooded my mouth, poured down my throat until I choked. When I could breathe again I glared at the terrible priest. Take me home now, I demanded.

Get in the chair, he lied, and we will turn around. I nodded, and then I started running. I did not even make it to the back of the chair before one of the men caught me. He slammed me back in the chair and the priest roughly held me in place. The men lifted me to their shoulders again.

I screamed for my father, and then my mother. We were walking through trees, and big leaves slapped at me. I considered grabbing one and climbing out of the chair. I got lost in a daydream about the leaves and the trees, and I could hear myself calling my grandmother. As I listened, my voice grew quieter and quieter.

Then there was darkness, and then a dream that my sister was pushing me, and when I awakened the chair was lurching back and forth. The wind was roaring, and before I even opened my eyes they ached from the ash it carried. It was inconceivably hot. I could hear the four men grunting. We were going uphill. We were on the mountain.

The ground shook, and when I reached out to steady myself, I realized my hands were bound together. I called out, I don’t even know what, and my voice was lost in the rumbling air and shaking earth. The men were shouting now. I could barely see the priest ahead of us.

The men carrying the chair kept stumbling and knocking me around. I was coughing too hard to cry. My entire body felt hot. One of the men was screaming, and I might have been screaming, too. Ash was in my mouth.

One of the men dropped to his knees, and I fell out of the chair. The ground was pebbly and hot. I blinked at it slowly until one of the men lifted me and staggered forward. Father, I thought, but I knew that was not right. But I was unable to think of any other words.

The man’s voice was coming in shouts now; I could hear it through his chest. He screamed and fell down, and then he carried me forward on his knees. He put me on my feet before he fell face down beside me.

Run, I thought. Go home. But I couldn’t see or hear. The hot wind surrounded me, filled my lungs and mouth. I felt hands on my shoulders, and the priest began pushing me uphill. Through the roar, through the shaking I could hear his voice, praying and crying. My eyes were squeezed closed. A boy was throwing rocks at me. I was on the beach, buried in sand. I was too close to the fire and Grandmother was scolding me.

I feared the earth would shake me off my feet. And then, with weak and shaking hands, the priest pushed me into the heat. I fell.

And then the ash swept through me and became me. My hands were unbound, but I no longer needed them. I was the mountain and its daughter.

The heat curled around me and said, What now, little one?

Cradled by smoke and fire, I thought of my family, and the children playing on the beach, and the boys in the boats. The adults touching my hair and smiling down at me in the market. All the strokes to my hair, all the touches to my cheek. Everyone watching me ride away.

Take them all, I said.

And the heat raised me up, and with a sound like thunder we made my greatest wish come true.