I don’t wish to raise unpleasant topics. But here in Paris in the early 1800s, we could use something to lift our spirits and bring us all together.

I have the perfect idea. We should build an ossuary! It’ll be like a subterranean craft project, using dead people.

If anyone can build a stylish monument out of human bones, it’s Parisians. We are already equipped with a certain elan and joie de vivre, not to mention je ne se quois. And sacre bleu, do we have the raw material.

Hear me out, mes amis. This is going to be awesome.

You Guys, We Have the Ingredients to

Build an Ossuary

In 1774, as I’m sure you remember, we had an unsanitary little problem. If you had to inhale anywhere near the Les Halles neighborhood, you were well aware of it.

Holy Innocents Cemetery, which we had been using since the Middle Ages, was full. It had been full for quite some time. By the 1770s, our burial method was just digging a pit, throwing corpses in, and then not covering them up for several months until the pit was full. Then we’d move on to the next big hole. Every five years or so we would dig pits back up and transfer the bones to the charnel house at the edge of the cemetery. That way we could reuse the same space, which is just smart thinking.

This open-pit-of-decaying-bodies system made the area unpleasant. Locals said that the putrid air could make meat rot as you watched. In any case, it was unhealthy for the neighbors, and even the passersby. Not to mention those buying groceries at the open-air market right next door.

To review: the air was disgusting, our former neighbors were rotting in open pits, and bones were beginning to fill up the charnel house. And then things got worse. It began to rain.

You might remember the spring of 1774 as especially rainy. If you lived beside Holy Innocents Cemetery you certainly do, because that was the spring the retaining wall broke open and wet cadavers spilled into your basement. Those Christmas decorations will never be the same.

The rains also brought us another problem. It, too, was underground.

We Totally Have the Space to Build an Ossuary

While the cemetery was literally bursting at the seams, the city was also collapsing.

The architecture of Paris was built with limestone. In Roman times we discovered an abundant supply, 85 feet below the surface. To create our city we dug a labyrinth of mining tunnels, 190 miles’ worth.

We sensibly kept our burrowing outside the city. But Paris kept growing, and eventually it sprawled over the mineshafts. We continued using the stone from below in buildings up above. And then, as anyone who has ever played Jenga would predict, the mines began caving in.

One terrible day that rainy spring, an enormous sinkhole swallowed up an entire city scene. Houses, traffic, and citizens disappeared into the earth.

Right away we got to work inspecting and renovating the mines. While we were shoring up the city, we looked around and noticed all the unused subterranean real estate.

So we started another project. This one only happened at night. Wagons draped in black, accompanied by a priest, went back and forth between Holy Innocents Cemetery and the mine shaft entrances. And when we had stored all of the bodies in the mine shafts, we moved on to the next brimming graveyard. We emptied five cemeteries in all. What we were now calling catacombs also welcomed the newly dead, which for reasons I’m not going to get into has come in handy.

We’ve got the bones of six or seven million people down there now.

Let’s Build an Ossuary!

We have solved the problems, but we have wasted an opportunity. I propose a third project: We should build an ossuary.

Strictly speaking, an ossuary is just a collection of bones. An ossuary could be a big box, or a charnel house. But let me tell you about what the rest of the world is doing.

Every country that holds onto their dead people, and has also had a plague, has a postmortem space issue. Countries as far-flung as the Czech Republic, Portugal, and Peru have solved them with ossuaries. Frequently in churches, but sometimes freestanding, people have been building monuments to their dead, using their dead. These astonishing, eerie, gorgeous ossuaries serve as places of contemplation as well as memento mori. And they are tourist attractions — visitors come from miles around to admire the elegant arrangements of bones.

And in Paris … we keep our dead in a mine shaft, stacked like firewood?

Come ON. We’re Parisians. We are more than just good diggers. We appreciate beauty and art, and, as recent times have shown, dramatic displays.

There is a reason the English language didn’t bother to translate chic and panache and sangfroid. When it comes to effortless style, the French are the envy of the world.

So let me ask you: Are we going to allow ourselves to be outdone by Portugal? Or Peru? That’s not even a country yet!

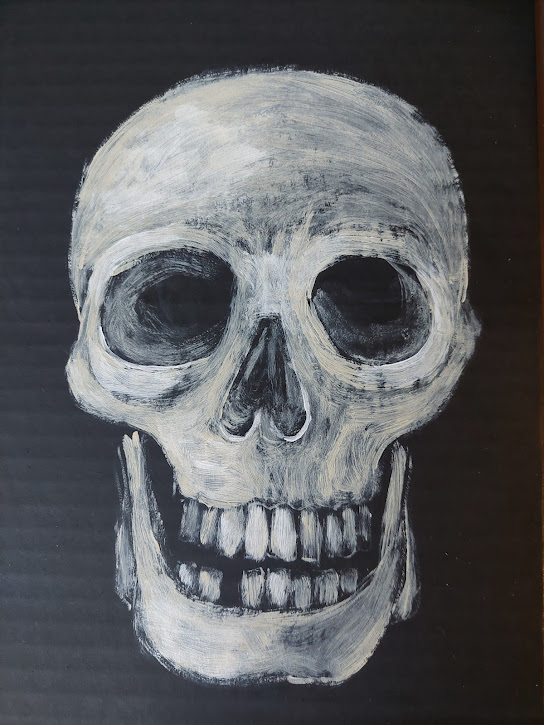

Let’s create something amazing. We’ll start small. We’ll pull a few bones from the pile, say a tibia and a skull, and affix them to a wall. I think we’ll find ourselves hooked.

Here’s what I’m envisioning:

And when we have created this memorial, we can let visitors to the city admire it. It will be a unified art piece, comprised of millions of dead Parisians working together. Their bones will be intertwined, their skulls will sit side by side, the noble born indistinguishable from peasants. We will honor our dead through beauty. And anyone who looks at our ossuary will come to the understanding that no body is better or worse than another. If that’s not Revolutionary, you guys, I don’t know what is.

Leave a Reply